Butterflies swooped and swirled above us. I leaned out over the moss casement stones of a former Portuguese fort and watched as the creatures -- mere silhouettes -- danced in the early spring dusk.

''They are bats, not butterflies,'' my friend R.W, announced.

Of course, bats. Situated in an austere hilltop fortress, that over the centuries has withstood many invasions and much political intrigue, the Castelo de Korlai seems an ideal place for a few bats. Stone seals from that time are still standing, but the etchings have eroded and are less defined; and the remains of the fortress walls are coated with moss. Silence rings through the waist high weeds-green, dense and prickly. I get entangled in the vegetation and yet I walk forward. Thorns pierce through my socks as I brush off the pollen. A rash breaks out as my arms glow red. I know scratching will not help but do not fight the stimuli. I have realized that in nature’s eye humans are an invasive species. A bulbul watches us from her ivory tower in the mango tree laughing at our endeavor to pierce the wall of green. Here we are on a ruined Portuguese fort on a hill, surrounded by the Arabian Sea on three sides. It is a place fit for a water colour painting. If the scene was not picturesque enough there is a lighthouse in the foreground added for good measure.

[The lighthose and fort of Korlai. The lighthouse keeper will give you a tour of the place for a mere 5 rupees.]

You would be surprised to hear that I am not in Korlai for the views or even the crisp Arabian Sea breeze. I am in Korlai, in a search for haunted forts, fallen churches and a lost Portuguese Creole soon to disappear. A short bumpy drive south of Alibaug, past the green glades of Revdanda and just before the Casuarina ridden beach of Kashid lies the quiet village of Korlai. A small community of a less than a thousand people in Korlai still speaks a language unique to them and different from any other language spoken in all of Maharashtra. It is a Portuguese Creole called Kristi that the locals refer to as No Ling, meaning our language. Through colonial expansion in Asia, Portuguese spread as the language of trade, which is how the language developed in the area. The Portuguese left the area in 1740, after which there has been little contact between the local community and Portugal. Yet the language has continued nearly three centuries on due to the relative degree of cultural isolation faced by the village. For many years Korlai and its Christian inhabitants, were relatively isolated from the Marathi-speaking Hindus and Muslims surrounding them. Since 1986, there is a bridge across the Kunkalika River, and the place has become more accessible and with it the more dominant languages such as Marathi and Hindi are increasingly being adopted. Like in Daman and Diu where a similar Portuguese Creole was once spoken, the unique Creole of Korlai is slowly fading away.

During the three days I spent in Korlai last weekend, I often felt as if I were walking around in a historical preserve, not a village. Or in an Indiana Jones movie or in frontier town of some faraway colonial outpost. I decided to let my feet lead me through the sepia-toned side streets of Korlai in search for this disappearing language. Having no prior experience at this sort of thing I decided to wander around hoping to chance upon the language and the light eyed people who speak it.

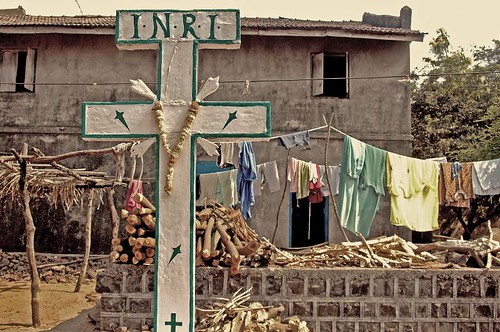

The streets were gray and of concrete, the homes were of brick and cement, and both were built on a narrow strip of land that expanded more and more until it suddenly curved and ended at the sea. Crosses punctuated every street corner. Old ladies in nine yard sarees oiled their hair, while children chased piglets and men sat cross-legged at porches tugging on beedis.

I smiled and walked on before I piqued one man’s attention enough for him to launch into a question. “Bon dee-ah”, he said before changing over to Marathi and asking me where I came from. Bon dee-ah I repeated as I smiled. There it was the simplest example of Portuguese where you least expect it with a dash of Marathi. I wanted to hear more of this strange pidgin so I was directed to the church and told to ask for a woman named Celestine. She will sing you a song I was promised, so we trudged along. Celestine was a cheerful old lady dressed in a purple sari. She looked well into the eighties but had an infectious demeanor of someone in her twenties and when we asked her to sing for us she was only happy to oblige.

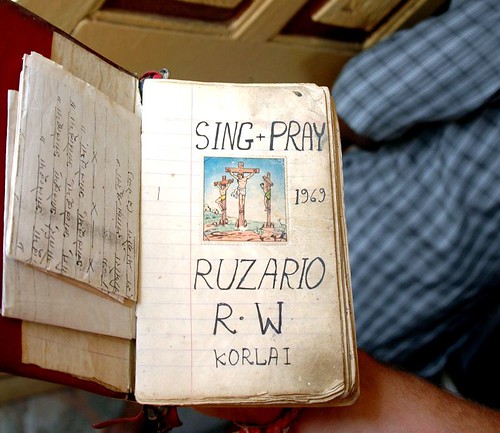

She sat us down just in front of the altar of Korlai’s old church and picked up a worn out looking note book from one of the drawers. As we settled down on one of the creaky benches of this old church she began to sing. In an aging baritone words curled out with a beautiful melody. This was the song of Korlai, a song in ancient Kristi.

“Maldita Maria Madulena,

Maldita firmosa,

Ai, contra ma ja foi a Madulena,

Vastida de mata!”

Which when loosely translated into English means :

Cursed Maria Madalena,

Cursed Beautiful one,

Oh, against my will it was Madalena,

Dressed in leaves and branches!

This was a haunting song about Maria Madelena; the song just like the language it was sung in are mere Ghosts of Portugal in Maharashtra soon to disappear.

* Published in the Hindustan Times, 1 February, 2007

Unknown

Hi, We are templateify, we create best and free blogger templates for you all i hope you will like this blogify template we have put lot of effort on this template, Cheers, Follow us on: Facebook & Twitter